The Path to Jarvis Part I

Existing communication channels between the human brain and machines have insufficient bandwidth to express the entire space of human ideas.

To solve this problem, we need to introduce a new machine-readable communication stream with higher bandwidth. There are two approaches we can take to this:

- Create an entirely new communication stream

- Adapt an existing communication stream with high bandwidth to a machine-readable format

Today I’m going to talk about the second approach. In particular, I’ll talk about what it will take to build an effective semantic parsing system. I’ll likely return to this topic in later Thoughts, but for now, I’ll describe the basics. For one, let’s make it clear what I mean by “semantic parsing”: semantic parsing is the task of converting utterances in natural language to statements in a formal language. In the context of human-computer symbiosis, this means converting sentences and phrases spoken in common languages like English or German into explicit instructions for the computer to perform, usually passing through the syntax of a pre-existent logical or programming language.

The fundamental problem is that human language is fuzzy, idiosyncratic, and ambiguous, which is particularly ill-suited for specifying instructions to machines. Computers require clear, precise instructions that fit a predictable syntax to reliably perform their duties, so if we’re going to build a more natural human-computer interface based on the high-bandwidth channel of human language, we need a way to convert fuzzy statements from natural language into concrete formal structures. This is the basis for semantic parsers.

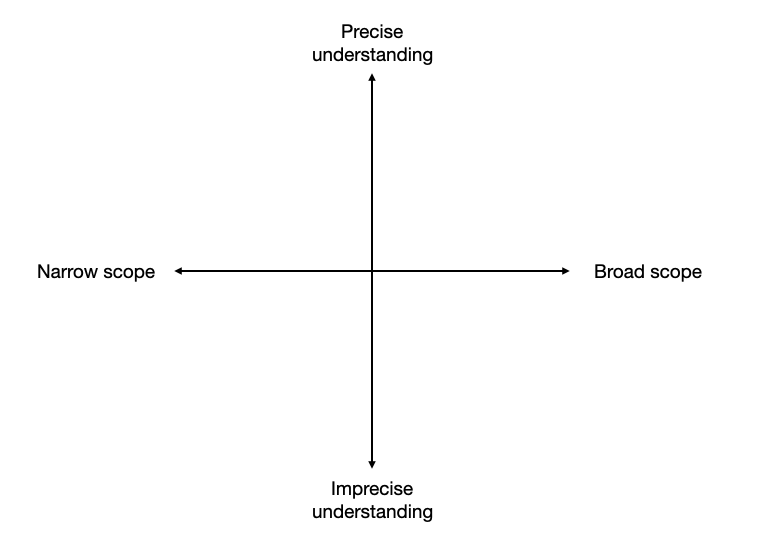

Before we go about building a semantic parser, we should understand what a good one would look like. To get a rough idea of what makes a good semantic parser, we can evaluate along two dimensions: (1) precision of understanding, and (2) broadness of scope. In other words, the semantic parser should understand what needs to be done and be capable of doing lots of useful things. To get a lay of the landscape, you can plot semantic parsers along these axes:

Our target is to build semantic parsers that sit in the top right: these are the Jarvis-like personal assistants which consistently answer queries correctly and resolve most of our mechanical intellectual needs. Unfortunately, I would say most semantic parsers today sit on the line $y = -x$: we’ve been able to build parsers that are either really good at a specific/idiosyncratic task (if you’re interested, check out Chat-80) or capable of a lot of really simple things without generalizing well to complex inputs.

To fix this, we’ll want to build a semantic parsing system with the following properties:

- You should be able to communicate as naturally as possible—there should be no requirement to learn an unnatural version of English (or any other language) to interact with it

- The system should generalize to any sequence of digital tasks a human could tell another human to do

- It should know when it doesn’t understand an instruction or its instructions are ill-specified

We can look at these one-by-one and try to get an idea of what we can do.

Natural communication

Banning unnatural sublanguages completely eliminates the relevance of rule-based systems. We can’t expect to solve this problem by mapping formal languages onto grammars of common words that admit sentences that look kind of natural. Because day-to-day communication is fuzzy, our models need to be able to handle fuzzy inputs to be sufficiently expressive. This means we’ll have to rely on statistical methods to infer the true meaning of sentences. Fortunately, this isn’t trading off much and statistical methods have improved dramatically in the past 5 years.

Generalization

Most digital tasks humans perform are not easily specified by a single formal language. Theoretically, we could build a programming language that simulates human control of a desktop computer by moving a mouse and sending keystrokes (simulating typing), but this still suffers from a failure to generalize to mobile devices or other machines that are controlled remotely. It seems inevitable to me that a sufficiently expressive semantic parsing system will support several target languages and adapt to new languages that arise as the landscape of downstream applications continues to evolve.

Most computer applications are reasonably complex and require non-trivial formal syntaxes to express the space of possible instructions. For example, the grammar defining VBA (a programming language used to script Microsoft Excel) is roughly 1000 lines long, and of course the space of possible programs is infinite.

To deal with this kind of complexity and dimensionality, we need lots of data. In particular, we needs a spanning set of pairs of natural language utterances and their corresponding formal statements. Fortunately we can generate an infinite volume of formal statements, but these are expensive to annotate: most use Amazon’s mechanical turk service to label data, which in this case would cost at least $0.70 per label assuming you’d hire labelers with a bachelor’s degree (I think this is reasonable since you’d require them to learn the formal language, which may be quite complex).

We can reduce this cost by designing high-fidelity synthesis systems that generate formal statements and corresponding natural language tags. I think this approach is promising if we stay focused on developing automatic synthesis/annotation methods that generalize to more formal targets.

Knowing what you don’t know

Self-consciousness is necessary in any field deployment of a semantic parser. The literature here is comparatively sparse, but I’ve been pretty excited by recent developments in Bayesian methods of machine learning. The scaling problem still needs to be solved for these approaches to be practical, but fortunately they allow us to inject prior notions of uncertainty that are progressively refined as the model observes more examples.

There are at least three huge benefits to this approach:

- We can define abstention protocols that prevent the model from executing formal instructions it’s unsure about

- We can get a sense for deficiencies in the distribution of training examples

- We can bring humans into the loop more effectively as models actively learn in the field.

Most semantic parsers these days predict formal language tags through a probability distribution over a vocabulary of tokens. For now we can use statistics on that probability distribution as a proxy for confidence, but I’m really excited to see what we can do with more sophisticated uncertainty measures as the logistics of Bayesian methods improve.

Summing up

An effective semantic parsing system would propel us much further towards a world of human-computer symbiosis. To do it right, we want a system that understands natural language as it is, is hyper-capable, and knows about its own fallibility. To make this happen, we’ll need a confluence of research initiatives. In the end I think the payoff would be enormous, and I’m really excited to watch the field progress.